Akki expects Hytone to begin producing electricity in January and to receive solid waste permits from the state Department of Energy and Environmental Protection (DEEP) by the second quarter of 2023.

Hytone is expected to generate 3.7 million kWh of electricity per year, which is enough to power 342 homes, according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

A main benefit of biogas power, Akki said, is that it has a positive impact on the environment by generating renewable electricity while also diverting food waste. The electricity produced is considered to have negative net emissions because it actually removes greenhouse gasses.

By capturing the methane and converting it to carbon dioxide, biogas facilities generate electricity while preventing methane from escaping into the atmosphere.

“Our gas is actually net negative, it reduces the greenhouse gasses because the methane that the manure would emit, or the methane that the food waste would emit in a landfill, are not being emitted,” Akki said.

In addition, Hytone will receive tipping fees from waste suppliers, which now have to transport food waste to landfills in other states. The facility is expected to divert 20,000 tons of food waste annually.

About 10% of the electricity Hytone produces will be used by the farm. The rest will be sold to the electric grid at a discounted rate through virtual net metering credits.

While anaerobic digestion technology has existed for decades, Akki said the costs to build a biogas facility are high. It has only recently become economically viable with the help of renewable energy credits and virtual net metering, she explained.

“It’s really important to build the business model to pay for it,” Akki said. “You haven’t seen or heard of a lot of these because it costs millions of dollars to install these systems.”

Connecticut has begun providing incentives to biogas power operators, such as virtual net metering, which allows a renewable energy system’s owner to share the billing credits that are generated when the system produces more power than the owner uses. The excess energy is fed to the electrical grid.

“The (agricultural virtual net metering program) really helps us,” Akki said. “Electricity becomes a source of income for the project to pay for it. And number two, the food waste ban — that food waste cannot go into landfills — also helps us, so we get tipping fees for food waste to pay for the project. Those income sources justify the project; otherwise it’d be very difficult, and even then it’s still pretty tight. That’s why you don’t see many of these projects.”

In July 2011, the DEEP implemented a new law that bans the disposal of commercial organic waste by businesses and institutions that dispose of 2 tons or more of these materials per week. Instead of landfilling that organic waste, state law now requires it to be recycled.

Since the July 2022 closure of the Materials Innovation and Recycling Authority’s Hartford trash incinerator plant, most food waste is being trucked outside of the state, Akki said.

Hytone Ag-Grid obtained loans and grants to help cover the approximately $5 million in construction costs, she said.

In addition to revenue from tipping fees and energy sales, Hytone receives income from renewable energy credits. It also received a $3.7 million Rural Energy for America Program loan from the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

Akki said she expects the return on investment to be five to six years.

Another challenge for the project has been the extensive permitting process. It’s taken more than a year to obtain regulatory approvals for the Hytone project, Akki said.

Limited land, best use

New Britain will be among the beneficiaries of Hytone’s lower-cost electricity. Stewart said electric bills for the three schools to be powered by Hytone will be about 30% less expensive than normal.

“What Ag-Grid Energy does is unbelievable, and it is definitely a new way of producing energy, but yet solving multiple problems in our environment, and we’re really grateful for that,” Stewart said.

Hytone Ag-Grid LLC is a special purpose entity created to develop, build and partner in the supply and operation of Hytone’s anaerobic digester at 2047 Boston Turnpike. The partnership is between Hytone Farm LLC and Akki’s company, Ag-Grid Energy. The digester system sits on about 6 acres, which Akki’s company leases from the farm.

“The farm is the equity partner in the entity, so they benefit and we benefit,” Akki said.

Greg Peracchio, owner of Hytone Farm, said he considered other ways of using his land to generate electricity, such as installing solar panels. But generating the same amount of power would require hundreds of acres — land that he needs to grow crops to feed his livestock.

“In the state of Connecticut, land is a limited resource,” Peracchio said. “There’s only so much of it available. And we need that cropland to be able to grow the crops that we’re using to feed the calves. So the solar panel thing, if somebody wanted to put them on a roof on a barn, a big barn with a big open roof, that sort of makes sense to me. But as far as putting in a solar installation on the ground, it doesn’t really make sense to us.”

Solar panels require about six times more land than an anaerobic digester system, Akki said.

Peracchio said he and his father once agreed they wanted to figure out a way for the farm to generate its own power and become more self-sufficient. Hytone Ag-Grid not only produces more than enough electricity for the farm, it creates a digestate byproduct the farm will use to nourish its crops. That will reduce the farm’s reliance on commercial fertilizer, saving money, Peracchio explained.

Creative energy solutions

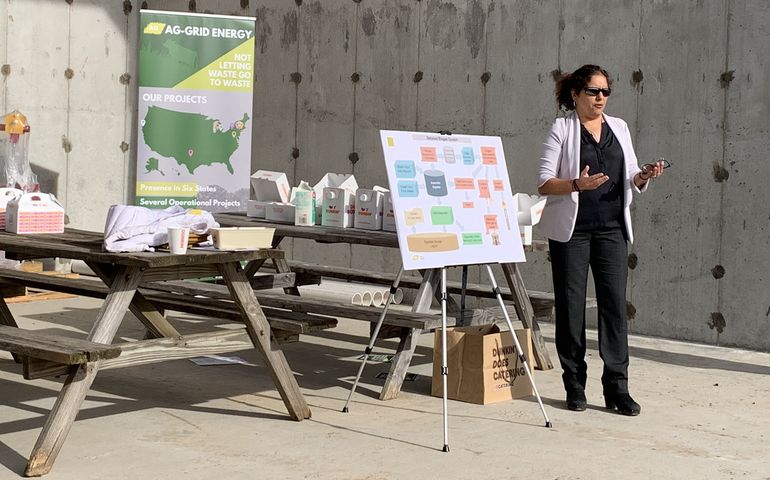

Ag-Grid Energy has other anaerobic digesters on dairy farms in Rockwood and Belden, Massachusetts and Lent Hill, New York. The company employs four people and has anaerobic digester projects underway in Michigan, California and Pennsylvania.

Ag-Grid Energy currently produces a little more than 2 megawatts of electricity across its facilities, heading toward 4 megawatts by the end of 2023, Akki said.

Alternative clean energy forms have been top of mind in Connecticut as energy rates rise and supply shortages in Europe threaten to cause electric disruptions this winter.

Connecticut has the third-highest average electricity retail prices among the lower 48 states, after Massachusetts and California, according to the U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA). Most of its electricity comes from natural gas-fired plants.

Renewable resources provided about 5% of Connecticut’s electricity net generation in 2021, according to EIA.

In 2019, Gov. Ned Lamont issued an executive order requiring 100% of the state’s electricity supply to be generated by renewable resources by 2040. The General Assembly codified that pledge into law earlier this year.

Stewart said she sees the need for creative energy solutions in Connecticut and hopes Akki’s project is a step toward expanding the state’s energy portfolio.

“As we’re looking at changing our thought process about how we get rid of waste, and how we produce electricity, having this type of biogas solution that may even be able to take our organic waste someday … really can get everybody thinking,” Stewart said.

View source version on : https://www.hartfordbusiness.com/article/coventry-dairy-farm-converts-manure-food-waste-to-renewable-electricity